It’s great when terms from your computer science education come up in day to day life. Tonight, I saw The Hobbit for the first time. I typically despise 3D films – I find the effect detracts from any cinematic creativity, distracts from screenplay and creates a novelty crutch for film makers to lean on. The Hobbit is the first 3D film I’ve ever seen that doesn’t suffer from this phenomenon.

The visuals in The Hobbit are stunning. Set in New Zealand, the epic scenery comes as no surprise – but just how much the 3D format adds to this enjoyment has to be seen to be appreciated. I’ve read that the 48fps format makes 3D more immersive and engaging, and having seen it first hand, for me this seems to be the making of 3D as a medium.

For those of you already familiar with the concept of 48fps movies, skip a paragraph – here’s what it means in layman’s terms:

Regular films are shown in 24 fps, or ‘frames per second’ – that is, 24 still images packed into every second make up the movie. The Hobbit is the first move to be shot and projected (in good cinemas..) at 48fps – double the normal speed. This difference is still perceivable to the human eye.

The vast majority of scenes in The Hobbit look spectacular. Cameras panning through scenery, orc-filled battlefields and vast citadels build into cliffs all prove incredibly immersive in 48fps 3D.

What’s interesting to observe is how the more familiar scenes look ‘a little off’. Pressing through a busteling marketplace, walking along a grassy path, a character standing in the doorway – none of it seems quite right.

But what’s happening here? Why do some scenes look so incredibly immersive and real, and some just look – well, they look plain uncanny.

Enter the “uncanny valley”. I first came across this term in the context of computer animation, but I think the theory also applies here.

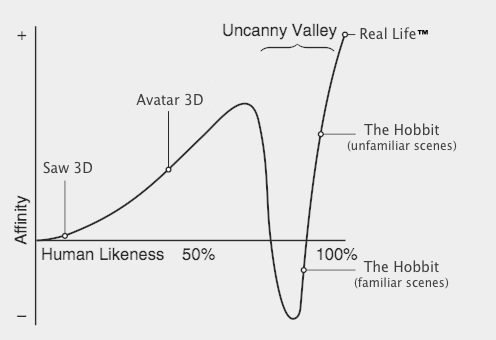

The Uncanny Valley applied to some recent 3D releases

The Uncanny Valley is the trough that exists where a scene is so close to human likeness, or in this case ‘real life’ likeness, that it appears unrealistic. It’s so close it’s uncanny, and our level of trust in the scene decreases, along with our affinity. This cliff which affinity falls off is the Uncanny Valley.

The reason action packed scenes and panning scenery all retain their authenticity is these scenes are unfamiliar to us. I’ve never encountered a battlefield of orcs, and I’ve never flown across the landscape hugging the ground in a helicopter. We have no prior experience which tells what these scenarios should look like.

It’s only when we see something familiar – the crowded marketplace, a person walking through a forest, all these scenes we’ve experienced frequently first hand, that we begin to feel uncomfortable.

The Hobbit in 3D can best be described as the reptile cabinet at the zoo. There’s clearly a large 2D plane which distorts our viewport, but the cinema screen has an almost translucent quality. Cinema has almost transcended this 3D barrier, and conquering the Uncanny Valley is the last remaining obstacle.